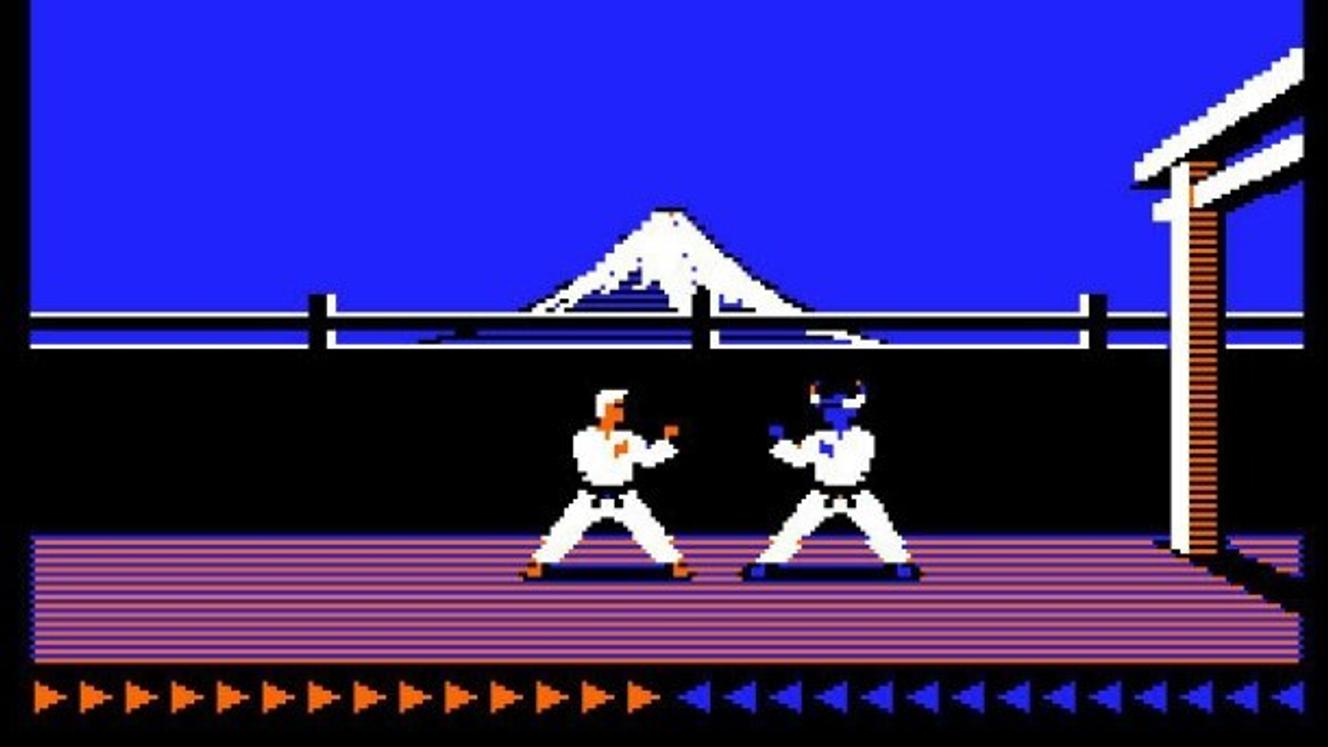

In the movie The Game of Death (released in 1978), Bruce Lee climbs the floors of a pagoda to fight a series of increasingly difficult fights against boss. Among the virtuoso filmmakers of Hong Kong, leaps and double leaps follow one another above the collision of blades, similar to the twirling acrobatics of platform games. If martial arts films seem to us today so close to video games, it is because the latter, from its earliest years, drew some of its most enduring refrains from these Asian cinematographies – like Karateka who, in 1984, invented by means of rotoscopy a video game equivalent to the technical apotheosis of the kung-fu film. The influence has become mutual, as the recent Sifua ruthless brawling game that pays homage to the famous « corridor dolly » of the Korean thriller old boy (2003), itself conceived as the horizontal scrolling of a video game.

A genre apart from martial arts cinema, the chabara (or Japanese sword film) is also an important reference in action video games, where samurai, ronins and other ninjas are recurring figures. katana duels Samurai Shodown (1993) to the sharp jousts of Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice (2019), the titles – mostly Japanese – taking advantage of the chivalric folklore of the archipelago are legion. But if most are based on heroic, delirious and grotesque gestures (like the series Onimusha), few have dared to be as literal with the samurai film as Karateka never had been with the kung fu movie. Recently, however, several titles claim this illustrious but difficult to honor heritage.

Back to classics

Among them, Trek to Yomi, which releases Thursday, May 5 (on PlayStation, Xbox and PC consoles), stands out with a grainy black-and-white image and an elegant sense of framing. Presented as a love letter to the films of Akira Kurosawa, this short title takes advantage of an aesthetic in paintings where the enemies arise like so many surprises from the confines of the plane. Its director, Leonard Menchiari, once again summons up the spirit of « cinematic » action-adventure games of the 1980s and 1990s, that of Kareteka and others Another World rotoscoped: he had already paid homage to the latter with The Eternal Castle in 2019.

The return to a more primitive form of the video game allows the cinephile Menchiari to work on scale ratios, transitions, games with caches and silhouettes, this time in the striking imitation of patina. chabara of the 1950s-1960s. Added to this is a documented reconstruction of the Edo period, as well as convincing borrowings from other cinematographic genres such as the jidai-geki (period film) or the kaidan-geki (fantastic movie). This quest for authenticity, right down to the exemplary soundtrack, will seduce connoisseurs. However, the cinematographic argument does not manage to deceive beyond the first hour, certainly attractive, of a fighting game which is based on clashes with sometimes frustrating repetitiveness.

It is because the use of the « Kurosawaian » model is here more a matter of image texture than of playful reinterpretation, just as was the case in 2020 for Ghost of Tsushimaa spectacular open-world game set in 13th-century Japanand century and based on exotic imagery. The blockbuster from the American studio Sucker Punch had been embellished with a « Kurosawa » mode, a filter allowing the image to be changed to black and white with contrast effects worthy of films in TohoScope, embellishing it with a sound more rough and squalls unleashing the elements as in the masterpieces of the Japanese master. Basically, however, Ghost of Tsushima remained an ultra-classic action game, a thousand miles from the rigorous cutting of the director of Seven Samurai. essentially staged in a sequence shot in the pursuit, hand-held camera, of a frolicking protagonist rather than that of a wandering ronin.

Beyond the edge of the sword

Like the game nioh (2017), envisaged at first as an adaptation of an unfinished script by Kurosawa having changed over the course of its development into a supernatural story that is ultimately very different, would the video game struggle to appropriate the codes of the cinema of Japanese sword? Notable exception, the very cinematographic saga Yakuza produced two sparkling episodes (unfortunately unpublished in France) set in feudal Japan, which owe as much to the dramas of period of the Japanese television than with the historical melodramas of Kenji Mizoguchi or that with The Legend of Musashi (1954) by Hiroshi Inagaki. Despite everything, the video game way chabara often remains confined to a stylized aesthetic that hardly goes beyond mere homage.

Remember that Akira Kurosawa did not only shoot black and white films and was not confined to saber films. Its characters are individuals who dare to reject the conventions of duty on which video games nevertheless like to develop their samurai figures. At Kurosawa, violence only intervenes as a last resort. At the end of Sanjuro (1962), the character played by Toshiro Mifune explains that « The best swords should remain in their scabbards ». Thus, the final duel lasts only the time of a flash and a spurt of blood. In Trek to Yomithe mentor is also called Sanjuro but he drags the hero to hell, in a series of battles accomplished in the name of revenge and redemption.

Beyond the humanism dear to Kurosawa, the samurai film is a cinema of the delayed attack, of ellipses, which is based on an economy of action. It is this singular grammar that Sergio Leone reappropriated with the spaghetti western, an expanded and picaresque version of the classic western, conceived according to the model of the Bodyguard (1961) by Kurosawa. The video game would undoubtedly have much to gain by operating such a transposition, considering the chabara not as a simple aesthetic filter but as an opportunity to reinvent the rhythm and staging of the action game. From 1984, the slowness and the postures of the duelist of Karateka outlined a cinematic playability that Trek to Yomialthough in line with this classic, does not quite manage to bring it up to date.